In Destiny Disrupted, Tamim Ansari tells the rich story of world history as the Muslim world saw it, from the time of Mohammed to the fall of the Ottoman Empire and beyond. He explains why our civilizations grew unaware of each other, what happened when the two civilizations intersected, and how the Islamic world was affected by the delayed recognition that Europe, long perceived as a primitive and disordered place, had somehow taken over its destiny This paper will reveal what happened.

Before the birth of Islam, there were two worlds between the Atlantic Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. One was mainly by sea, the other by land.

The first was the Mediterranean, for it was here that Mycenaeans, Cretans, Phoenicians, Lydians, Greeks, Romans, and many other vigorous early cultures met and mingled. People who lived in the immediate vicinity of the Mediterranean Sea could easily hear and interact with others who lived in the immediate vicinity of the Mediterranean Sea. Thus, this great sea itself became the organizing force that drew diverse peoples into each other’s stories and spun their destinies together to form the germ of world history, from which “Western civilization” was born.

The “Western civilization” was born in the Persian Gulf, the Indus River, the Oxus River, the Aral Sea, the Caspian Sea, the Black Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, the Nile River, the Red Sea, and soon. This eventually became the Islamic world.

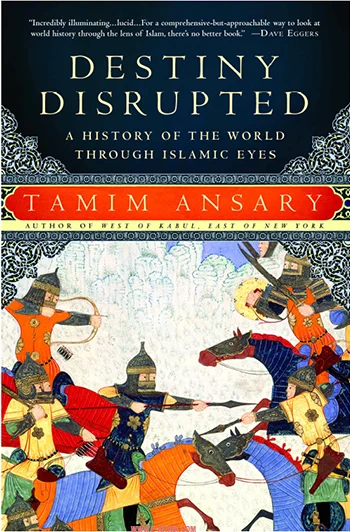

About the Book

Some writers are meticulous about which method they use to translate Islamic names and words into English and insist that one or the other is correct. I confess that I am not one of those people. I have seen too many different spellings of my name in English to be particular (I am often asked which is correct, Ansari or Ansari, y or z.I am often asked.) Given the arbitrary nature of transliteration, the simplest spellings and most straight forward notations have been the guiding principles in this book.

Many Arabic names also contain a series of patronymics beginning with Ibn, meaning “son of.” I usually use the shortest form of the name by which the person is most commonly known.

Unfamiliar names (and words) in this book Many English-speaking readers will have difficulty with the large number of unfamiliar names (and words) in this book. I want to minimize such difficulties, so when a familiar word or form of a name exists in English, I will use it. Also, following the precedent set by Albert Hourani in A History of the Arab Peoples, I use prefixes when Arabic names are first used, but not thereafter.